Great Ideas Don’t Persuade

A great offer coupled with a well-reasoned presentation will get your audience engaged and your customers lining up, right? Yeah, not so much.

The world’s most creative and important products, inventions, and solutions were nothing more than ideas until someone persuaded someone else to do something. Great persuaders bring ideas to life. Persuaders make things happen.

The greatest historical achievements ever created are the results of persuasion. The empire builders, the Caesars and Napoleons, won by persuading others to follow. Cities and civilizations were built with persuasion. Columbus persuaded Queen Isabella that he could reach the East, India, by sailing west; then persuaded her to finance his ships.

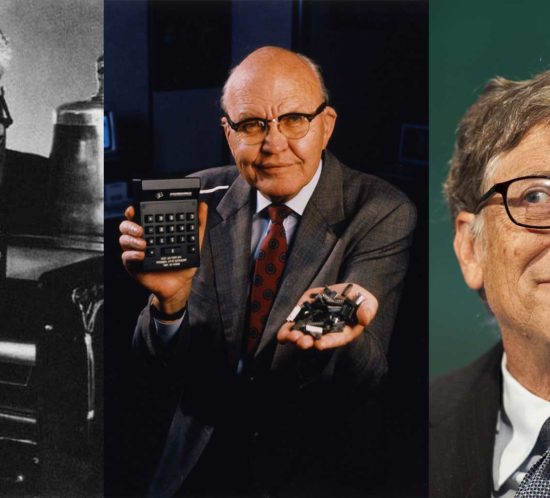

Douglass Persuaded Lincoln

If I can persuade, I can move the universe.

–Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass is largely credited for persuading Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. In so doing he used, according to John Stauffer, author of Giants: The Parallel Lives of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, one of the key foundational emotional triggers known for its persuasive power: Friendship.

“More than anything else,” Stauffer explains in an interview with NPR’s Michel Martin, “their friendship was utilitarian. Douglass recognized that he needed Lincoln on his side to help him achieve his chief aim of ending slavery and trying to bring about racial equality. He need the president on his side. Lincoln recognized that he needed Douglass on his side to help him achieve his chief aim, which is winning the war because Lincoln finally realized that in order to win the war, he needed blacks on his side. He needed blacks fighting for him. And more than anything else, that was the basis of their friendship because these two separate goals had converged. In order to win the war, you needed to emancipate slavery. In order to emancipate slavery, you needed to win the war.”

“Friendship was a term that was crucially important at the time because from, really, classic antiquity – from Cicero, Plato, Aristotle forward through the 19th Century – friendship was a central philosophical, political, intellectual concept. It was believed that a virtuous society was one in which friendships flourished. And especially in a democratic society, friendship was seen as a test case of whether or not democracy was working. And more particularly, interracial friendship was seen as a symbol of whether or not democracy could work. So Douglass especially promoted, championed his interracial friendship as a kind of test case, on-the-ground example of how democracy could work, and in his hope, an inspiration for others in the United States.”

Shared interests and mutual goals are a core tenet of successful persuasion, something great leaders – persuasive leaders – have used since time immemorial.

Kennedy Persuaded a Country

JFK persuaded Congress and the American public to support and fund a wildly ambitious plan to put an American on the moon. In a famous speech revered to this day as a paragon of persuasive rhetoric, Kennedy not only made the case for the endeavor, he set down a model of persuasive communication best practices.

In a useful and practical analysis of JFK’s “Why Go to the Moon?” speech, Experience to Lead founder Dick Richardson offers key insights into Kennedy’s tactics; into his ability to “appeal to the heart as well as the mind.”

“Kennedy used two organizing principles for his talk,” Richardson explains, “the first was chronology, starting with the past and ending with the future. The other was Aristotle’s three forms of persuasion: logos, pathos, and ethos — logic, emotion, and credibility.”

Richardson also points out some powerfully persuasive rhetorical devices used in the speech:

- Simple words. Kennedy doesn’t try to impress by using multisyllabic words no one recognizes. He makes the information he’s sharing accessible, understandable.

- Short sentences. Kennedy also uses short, crisp sentences containing a single idea at a time.

- Systematic. When Kennedy makes a statement, he then backs it up with an explanation or proof. He makes his point in a methodical way.

- No extra fluff. He chooses his words carefully, packing a punch in as few words as possible. He chooses words that generate an emotional response whenever possible, such as “pride” or “un-tried.”

- Repetition. Many of the great speeches, including Kennedy’s, use repetition for effect. Abraham Lincoln repeated the words “cannot” in the Gettysburg address: “Cannot dedicate…cannot consecrate…cannot hallow…” Similarly, Kennedy used the phrase “We choose” three times in his speech, just as Martin Luther King, Jr. used the phrase “Now is the time.

Read Richardson’s entire analysis here.

Watch key portions of Kennedy’s famous speech here:

But what happens when people can’t persuade?

Right—nothing!

Lack of persuasive power is a key factor in keeping otherwise outstanding people from achieving the success they deserve. Many great inventions—historical solutions, major medical advances, critical corporate change initiatives—each failed simply because the creator hadn’t acquired easy-to-learn persuasion skills.

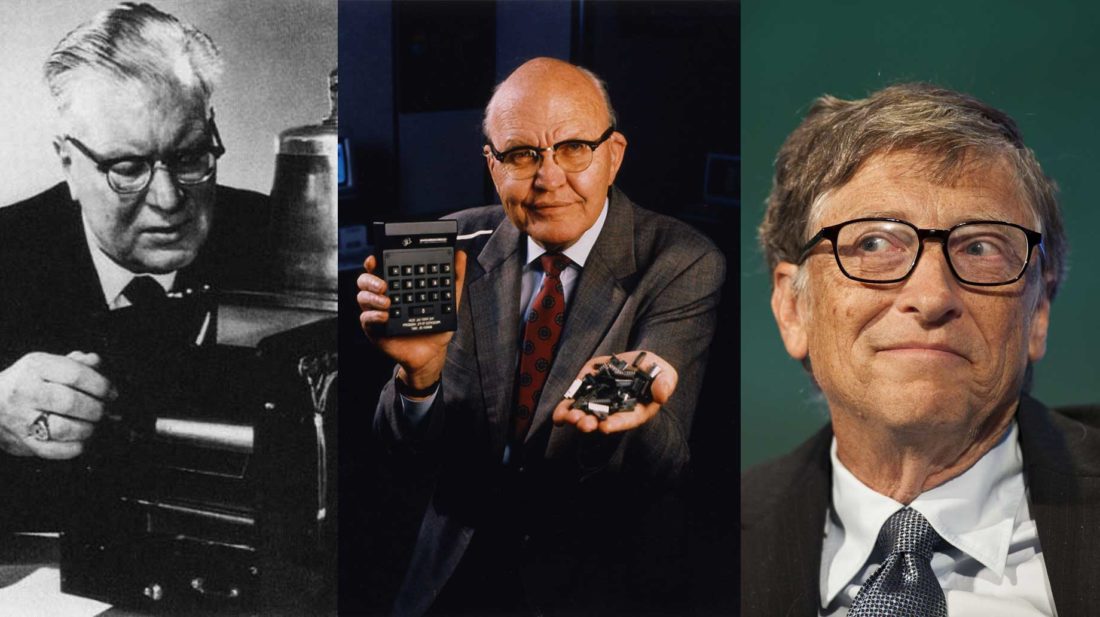

Carlson Persuaded No One

Are you smart? Maybe flat-out brilliant?

Do you have degrees from a top university? Do you have ideas that might improve your organization’s status… change your life…. change the world for the better?

You’re sure to be a success, right? Maybe not.

Gifted intelligence, great ideas, and outstanding products by themselves do not persuade. Even the most amazing scientific discoveries didn’t see the light of day until someone persuaded someone else to get the discovery into the marketplace.

Chester F. Carlson was a brilliant physicist, lawyer, patent attorney, inventor, and research engineer. But he wasn’t a persuader. Watch:

The Two-Trillion-Dollar Invention

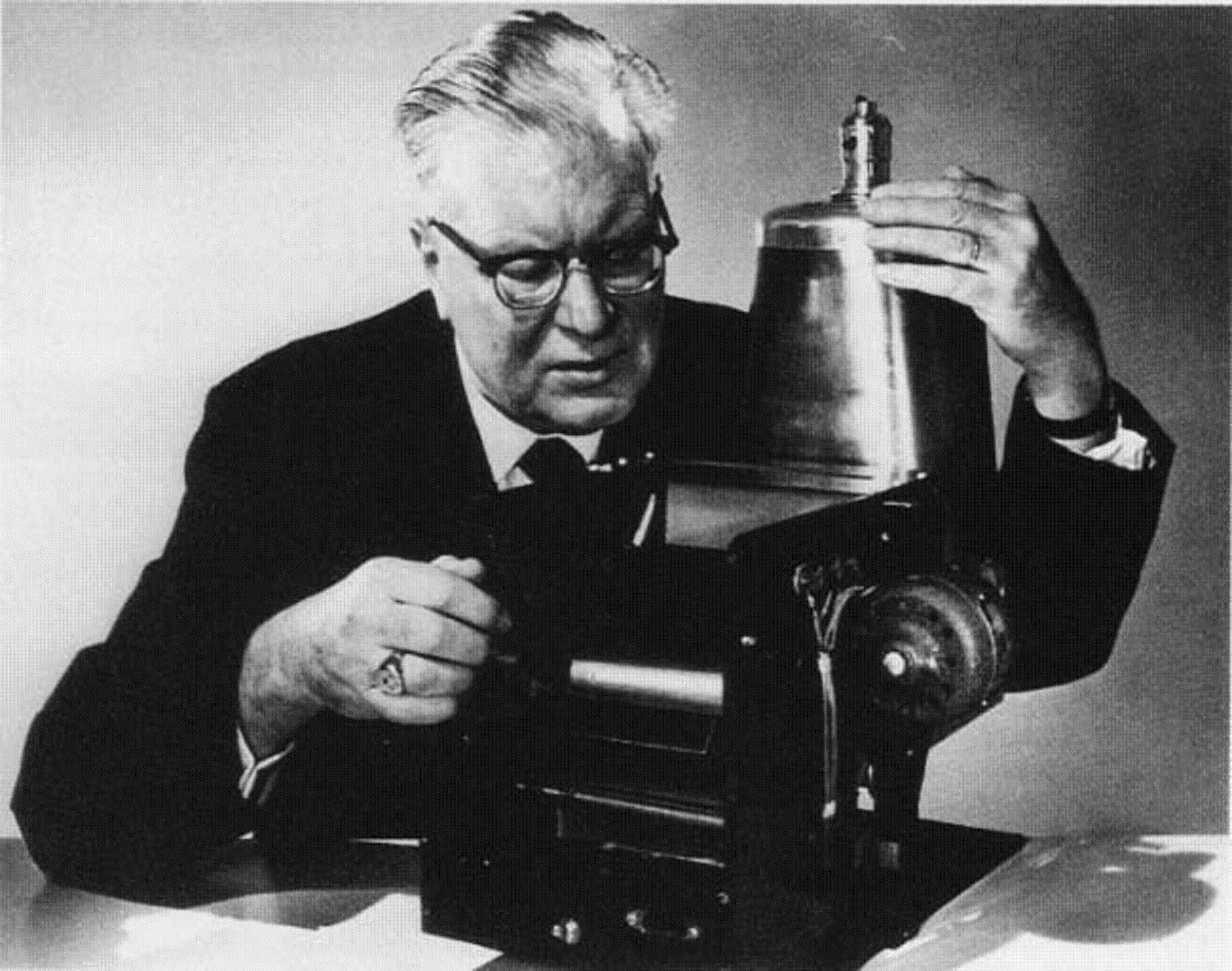

While at Texas Instruments Jack St. Clair Kilby received patent number 3643138 for his invention of the first integrated circuit, the forerunner of today’s computer chip. Impressive, right? Not so much… Kilby couldn’t even persuade his own company to implement the idea. “Don’t you realize,” he was asked by management, “that computers are getting bigger, not smaller?”

Because he was a non-persuader, for years his brilliant invention went undeveloped. In his autobiography, Kilby admits, “I worked hard with Robert Royce at Fairchild Semiconductor to achieve commercial acceptance.” But that didn’t happen. Even his savvy engineering skills could not persuade anyone to put his invention into any commercial application. Instead, Kilby acknowledged wistfully: “The integrated circuit provided much of the ‘entertainment’ at major technical meetings over the next few years.” The most important element in today’s entire electronic field provided merely “technical entertainment”.

A decade after obtaining his patent, Kilby was asked to make a calculator small enough to fit into a pocket. Using his integrated circuit, he invented the digital calculator and the chip had its first commercial application. Others saw the potential and persuaded companies to make new applications. A new electronics era was born. But Kilby’s lack of persuasive ability had kept this major technological breakthrough lying fallow, totally in the dark for more than a decade! Two critical inventions—the copy machine and the integrated circuit chip—went nowhere for many years because their genius creators weren’t persuaders.

Persuasion Naturals

But flip a coin. Try the other side. Let’s look at a situation where a great persuader had no product, only limited experience, and no credibility—not even a college degree. Yet, with persuasion, he would become the world’s richest man.

In 1975 Bill Gates was studying pre-law at Harvard. Meanwhile, his hobby was playing with early computers. Gates and boyhood friend Paul Allen noticed that the Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems Company (MITS) had developed one of the first mini computers—the Altair 8080. Gates contacted MITS and told them he had developed a BASIC program that would make their computer run better. Yes, it was a lie. He had nothing. Yet he persuaded the company to install his program in their computer. Gates had never seen the Altair 8080 and had never written a line of BASIC code. He didn’t even have the computer’s operating chip. Yet—with his persuasive ability—he convinced MITS to purchase a product that didn’t exist. Working around school assignments, for eight weeks Gates wrote code. He then flew to the MITS office and installed the untested program in a computer he had not seen until that day. To even his surprise, it worked perfectly! MITS now owned the newest BASIC program.

What next for Gates? Well, he simply persuaded MITS to sell him its BASIC program! Still a Harvard pre-law student, he realized the software industry was in its birthing stage. He next persuaded his parents to let him drop out of Harvard, and persuaded Paul Allen to join him in a two-man venture. Microsoft was born. And Gates has since been described as the most influential person of the twentieth century and beyond. Persuasion is influence!

By contrast, Carlson and Kilby had everything but persuasive ability. Each had an incredible product, patented and ready to go. Each had impeccable credentials. Yet they were flat-out stymied for years. Gates—with little but an idea, a keen technical mind, and inherent persuasion skills, quickly built the Microsoft empire. He started a company on an idea and persuasion.

Persuade or Perish

It matters little how necessary, creative, innovative, outstanding, or even critical your ideas, solutions, visions, or products are. If you can’t get someone to execute, you won’t succeed. Persuade, motivate, gain compliance, and your ideas might well catapult you into fame, fortune, and self-fulfillment.